STEM and ELT: 4 Science Strategies

This post covers the final four strategies in my STEM and ELT series. The strategies I discuss here, including the four strategies from Part 1 of this series and the seven science reading strategies from my November Blog, are intended for immediate use in your classroom. These strategies have been gathered from various sources, such as the 2008 book Science for English Language Learners: K-12 Classroom Strategies (edited by Fathman & Crowther) and research by the National Academy of the Sciences.

As a reminder, here are the nine strategies for teaching science to ELs. Strategies 6–9 are covered today.

- Connecting With Students

- Teacher Talk

- Student Talk

- Academic Vocabulary

- Reading Skills

- Writing Skills

- Collaborative Learning

- Scientific Language (Engaging in Discourse)

- Process Skills of Inquiry

Remember, these strategies are listed and explained individually, but for English learners (ELs) to gain a better understanding of the science content and the English language, the strategies should be used in combination.

6. Writing Skills

Science and STEM content classes contain a lot of academic language and require a lot of writing, from lab reports to journaling. This may be easy for native speakers, but for ELs it poses a challenge because ELs have to expend more time and effort finding the right words. Writing requires processing of language and a vocabulary database in order to construct sentences and produce a message. So, how can you assist your ELs in writing in the STEM content class? By adapting writing assignments so ELs can more easily provide their answers. Following are some ideas.

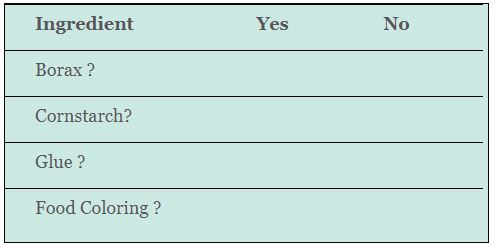

For lab reports, provide EL students with three to four logical choices in place of having them write out a hypothesis. Students can then select which choice aligns with their hypothesis by marking a box. This can also be accompanied with sentence frames or sentence starters to help them write why they chose their selection. The following chart is an example of logical choices for a hypothesis for a Bouncing Ball Challenge. The Bouncing Ball Challenge required students to complete a task to determine which ingredient(s) would make the ball bounce the highest.

Student Hypotheses

Sentence Frame Examples

- My hypothesis is that increasing/decreasing (circle one) the amount of ____________ will make the ball bounce higher. *Notice how the sentence frame used the academic word “hypothesis.”

- I reduced/increased (circle one) the amount of _______ from ________ (amount) to _______ (amount). The ball bounced ________ high. *Be sure to add units in your answers.

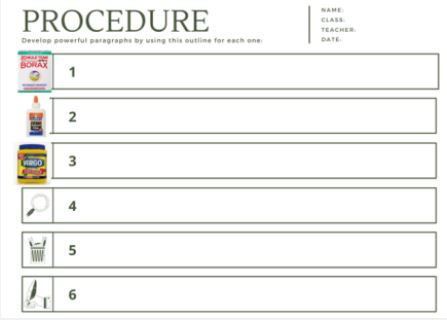

To aid the student in writing the procedure, allow the students to use pictures (provided by you) or to write the word to show the order they followed. See the picture in Figure 1 as an example.

7. Collaborative Learning

STEM subjects provide students with varied ways to not only develop new technical knowledge, but also many opportunities to read, write, speak, and listen to English, which is crucial in reaching language proficiency. STEM subjects allow ELs to engage in substantive conversations about what they are learning and to make connections between spoken and written practices.

Figure 1. Using pictures to aid in procedure writing.

We must remember that language is a product of interaction and learning, nor a precursor or prerequisite. When creating collaborative groups, teachers should be mindful of the students’ language proficiency and pair students accordingly. You do not want a group consisting of beginner or lower proficiency level students only. You want to be sure that there is a nice blend of proficiency levels and native speakers so that ELs can hear and learn content and vocabulary used in proficient speech. Here are some ideas on how to help ELs participate in collaborative groups:

- Be sure to set group goals and roles for each member.

- Set timers for each group so each member has an opportunity to speak or participate in the discussion. (Students with developing proficiency can be provided sentence frames and be allowed to draw, write, or use another speaker of their language to translate for them, if available.)

- Set expectations and clearly articulate the roles of each group member. For example, a recorder, reporter, illustrator (great assignment for beginner language level students), and spokesperson.

The bottom line is that you want ELs to know that they are an equal part of the group and that their opinions and participation matters. Every member of the group must understand that the group is interdependent and that their individual success is dependent on the success of the group.

8. Scientific Language (Engaging in Discourse)

STEM subjects consist of a lot of academic language, which is problematic to ELs. Pauline Gibbons, in her book Mediating Language Learning: Teacher Interactions With ESL Students in a Content-Based Classroom (2003), states that the more registers a student can participate in, the more the students’ growth in language. Registers are the way a person uses language in different circumstances, such as whole group, small group, pair work, and individual thinking time. Each of these registers requires a different type of speaking.

For pair work, students can use less sophisticated communication by pointing, drawing, and using body gestures. When working in small groups or with the whole group, they must use more sophistication of language to better articulate what they are trying to express. For example, the Bouncing Ball Challenge shows how students can practice various registers within one activity: The students work together to complete a few trials. They will then move from talking in small groups about what quantities they used and the height of the ball to explaining to the teacher or the whole group the process they followed in determining which variable created the highest bounce. The teacher can guide the students during these conversations by having ELs focus on key vocabulary words, asking for clarification using guided questioning, or restating. Here is a possible conversation between teacher and student:

Teacher: Tell us what you discovered in making your ball bounce.

Student: We changed amounts until ball bounced highest.

Teacher: Okay. Can you be more specific? Which amount did you use for each ingredient to get the highest bounce?

Student: We found that using more glue and did not change the other amounts.

Teacher: How many trials did you do?

Student: Three.

Teacher: So from your three trials you found that increasing the amount of glue gave the highest bounce?

Student: Yes. But we keep the other amounts the same.

Teacher: So, to use more scientific language, you only changed one variable at a time? Is this correct?

Student: Yes. We only changed one variable at a time.

The teacher allowed the student to explain using their own words, then asked for clarification before using the scientific words in context. Here are examples of sentence patterns that you can provide your students when engaging in discourse in the science classroom.

9. Process Skills of Inquiry

Hands-on, inquiry-based science is one of the best ways for all students to learn science, not just ELs. Carrying out hands-on science experiments or STEM tasks require students to use the process skills of observing, communicating, classifying, measuring, predicting, inferring, formulating, hypothesizing, controlling variables (as in the Bouncing Ball Challenge), creating models, and interpreting data.

Because ELs have varying backgrounds and levels of English proficiency, you may need to take steps to build the specific skills necessary for performing a particular inquiry-based activity. For example, for prediction, you could present the students with a sequence, but leave out a part of the sequence and ask the student to draw the missing part. Using the Bouncing Ball Challenge, you may have pictures of the ingredients with upward arrows to represent increasing the amount, a downward arrow to represent decreasing the amount, and a picture of the ball bouncing high or low. This can be done for each ingredient. The student can place the pictures in sequence to state their prediction. For interpreting data, you could create a table with the variables listed, the amounts, and measurements of heights the ball bounced, and have the students analyze and explain the data.

These strategies, including the ones listed in October and November’s Blog, provide you with ideas that you can use when teaching ELs in your science/STEM classroom. Without a doubt, the science classroom is a place where students have the opportunity to practice language in its context while simultaneously learning English. The science classroom provides students with opportunities to learn English using multiple registers and modalities because ELs benefit from multimodal interactions and diverse opportunities to learn.

Which one of these strategies are you going to try in your classroom?

About the author

Darlyne de Haan

Dr. Darlyne de Haan, a former forensic scientist and chemist with more than 20 years of experience in STEM, is a recipient and participant of the coveted Fulbright Administrator Program for Fulbright Leaders for Global Schools, a program sponsored by the U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. She is a strong advocate for changing the face of STEM to reflect the population and is fluent in English and advanced in Spanish.