Build Better Rubrics: A Teacher’s Guide To Effective Assessment

If you needed to weigh a bag of apples, you would place it on a scale. In this process, the scale’s job is simple: show the bag’s weight on the scale’s indicator in pounds and ounces, for example. Similarly, to measure language ability of students in our teaching practice, we need a “scale” that should function as accurately as possible: our assessment mechanism or plan.

If you needed to weigh a bag of apples, you would place it on a scale. In this process, the scale’s job is simple: show the bag’s weight on the scale’s indicator in pounds and ounces, for example. Similarly, to measure language ability of students in our teaching practice, we need a “scale” that should function as accurately as possible: our assessment mechanism or plan.

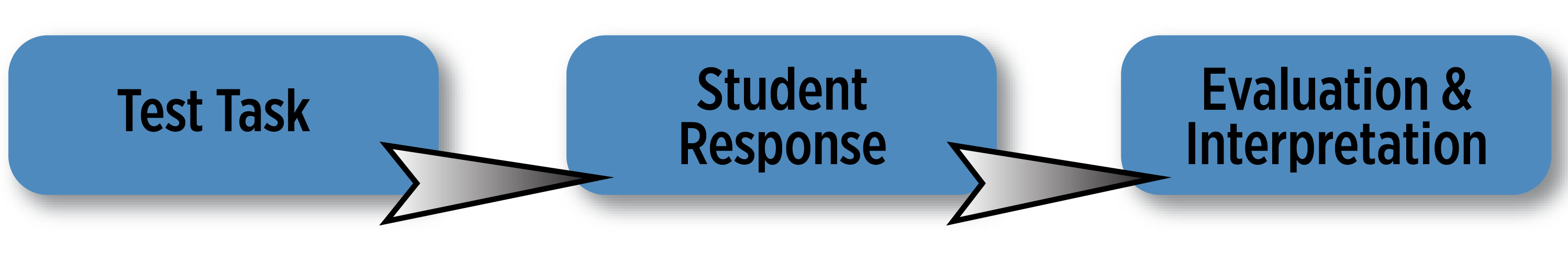

Language assessment measures students’ learning related to one or more skill areas (or constructs), such as expository writing, vocabulary knowledge, or listening comprehension. This procedure has two equally important components: a test task, like an assignment or timed test, and a scheme (criterion or standard) for rating and interpreting scores: Our effort and attention are often directed at developing test tasks, but a well-structured rating scheme—or rubric—is essential for effective assessment. To ensure your assessment is fair and accurate, you’ll need a well-designed rubric.

Our effort and attention are often directed at developing test tasks, but a well-structured rating scheme—or rubric—is essential for effective assessment. To ensure your assessment is fair and accurate, you’ll need a well-designed rubric.

What Exactly Is a Rubric?

Think of a rubric as a scoring guide that is an essential part of a test; it’s a structured tool used to precisely, consistently, and transparently rate students’ test responses. A rubric includes

-

- evaluative criteria,

- bands/levels on a scale, and

- standards for a cutoff score.

For test fairness and transparency, it’s important that stakeholders, especially students, can see how a test is scored and the final value is determined.

Rubrics are required for both selected response (e.g., multiple choice questions, true/false) and constructed response (e.g., short answer, essays, summarizing) assessment, but they are more important when students are creating something. A reliable, valid rubric should present clear and specific:

-

- test objectives,

- evaluative criteria,

- scores representing performance levels, and

- procedures for allocating and interpreting numerical values.

According to the research, rubrics also serve a larger purpose: They support student learning. With rubrics, students learn to critically engage with course materials, apply self-assessment, understand peer/teacher feedback, and develop autonomy as well as self-regulated learning.

How to Design a Rubric That Works

Rubrics aren’t one-size-fits-all. Every educator is different and every learning situation is unique, and your own professional intuition plays a big role in shaping a useful rubric. Here are some practical guidelines for designing a rubric:

- Start with a clear purpose. Begin by stating what you’re assessing. Be brief and specific. This statement serves as a guiding framework for enhancing validity and accuracy of measurement. Instead of “Rubric for Essay,” try “rubric for persuasive essay: Use of Evidence and Structure.” Being specific helps keep your evaluation focused and meaningful.

- Choose your rubric type. There are two main types of rubrics:

-

- Holistic: Gives one overall score based on general impressions, combining various criteria under one heading/level

- Analytic: Breaks down the score into separate categories, separating each criterion and specifically stating it (like grammar, organization, content)

-

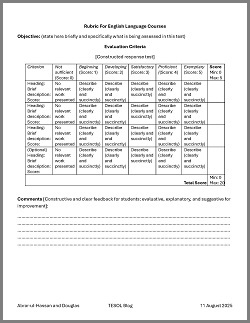

Both rubric types have strengths and limitations, and research has not established the effectiveness of one over the other. If you're looking for both detailed feedback and clear structure, we recommend employing an extended analytic rubric (EAR) that outlines assessment criteria, uses each criterion on a scale, and provides space for constructive feedback (see the EAR template to the right; download the template here [.docx]).

Both rubric types have strengths and limitations, and research has not established the effectiveness of one over the other. If you're looking for both detailed feedback and clear structure, we recommend employing an extended analytic rubric (EAR) that outlines assessment criteria, uses each criterion on a scale, and provides space for constructive feedback (see the EAR template to the right; download the template here [.docx]).

- Identify three to four criteria. Select the most important things you want to assess (e.g., features of a specific test outcome that are relevant to the test construct, as mentioned in Step 1). For each, include a heading,a brief description, and the maximum score.

- Describe performance levels. For each criterion, write five to six rating scale levels describing how students might perform. The descriptions should:

-

- use parallel structures and avoid abstraction (e.g., “excellent” or “good work”).

- use words/phrases that indicate observable features, like punctuation, topic sentences, coherence, and fluency.

- focus on performance quality (e.g., related to oral fluency, synthesis and reasoning, use of phrasal verbs, and others) rather than components of the test/task used.

-

- Assign point values. Give each performance level a numerical value. Avoid ranges (e.g., 3–5 points) and instead assign a specific number for every level. Also, set a passing score and explain how you determined it.

- Get feedback and test it. After an initial rubric draft, seek peer validation by inviting a critical review by a few fellow educators. Then, pilot your revised rubric on a small scale and reflect on its performance for further revision.

- Revise and improve. Rubrics should evolve over time. As you use them and receive feedback from students, colleagues, and educational administrators, update them. Rubrics as tools are based on conceptual ideas and levels: Regular revision will help improve rubric clarity, levels, and scoring. Finetuned rubrics can be integrated into course syllabi and learning management systems.

- Keep it simple and practical. Consider using these basic design features to make a rubric comprehensive but practical enough to implement:

-

- 1–2 pages long

- Based on 3–4 criteria

- Use 5–6 performance levels

-

- Don’t forget selected response tasks. Develop rubrics for all assignments/tests. We often skip rubrics for selected response format tests (e.g., multiple-choice or fill-in-the-blank types of tests). But even for these, we recommend developing a holistic rubric to help students understand their performance beyond just the number of correct answers. See the following example for a vocabulary test (selected response format) in an intermediate proficiency level ESL course:

|

Score range [out of 10] |

Level |

Description |

|

10–9 |

Proficient |

Understands and uses vocabulary accurately in context; few or no errors. |

|

8–7 |

Satisfactory |

Recognizes most vocabulary and uses it correctly; minor mistakes. |

|

6–5 |

Developing |

Basic understanding of vocabulary; may struggle with usage or makes some noticeable errors. |

|

4 or less |

Not Pass |

Limited vocabulary knowledge; frequent errors; difficulty using words in context. |

Rubrics Aren’t Perfect (But They’re Useful!)

A rubric isn’t as precise as a scale for weighing apples. It can’t measure learning precisely (e.g., down to the ounce, as with a fruit scale); with assessment rubrics, the difference between a score of 5 and 6 may not be equal to the difference between 4 and 5. Rubrics can, at best, rank performance levels—they can’t give us the precise intervals we might desire. Even with these limitations in mind, well-designed rubrics aid us in establishing accuracy, transparency, and fairness in assessment, and they can better engage students in their learning—and that’s positive for both teachers and learners.