Cultivating Belonging in the Classroom: 2 Practical Activities

As someone who researches identity and belonging, I have spent many hours talking to people about how they feel about their place in school and society and how they position themselves in relation to others. One adolescent girl from Samoa described how she felt on her first day of school in New Zealand: “I felt uncomfortable. It was my first time sitting in class and everyone around me spoke English. It was weird. Like watching a TV programme. I was just watching, and not part of what was happening.”

Fiafia’s experience is not uncommon among immigrant students and those who come from refugee backgrounds. An OECD (2020) report suggests that one in three students around the world do not feel a sense of belonging to their school. What is important is how we deal with these experiences, and work toward helping students to connect better to the school.

Students’ sense of belonging refers to the feelings of being accepted by teachers, peers, and any other individuals at school, and feeling like they are part of the school community. When students feel that they are a part of a school community, they are more likely to perform better academically and are more motivated to learn. Studies also show that the feelings of security, identity, and community associated with a sense of belonging affects students’ psychological well-being and social development.

While a sense of belonging is necessary for all students to succeed in school, students from immigrant and refugee backgrounds are particularly affected. Here are two classroom activities, adapted from Allen and Kern (2020), through which teachers can begin to cultivate a sense of belonging in the classroom.

Connecting With Teachers

Undoubtedly, student-teacher relationships form the backbone of students’ connections to the school. A trait that students appreciate in teachers is a strong sense of justice and fairness. This activity may help students understand that equality is not the same as equity. That is, teachers may treat students differently in order to be fair.

Activity 1: Band-Aid Solution

Begin by asking students to share a time when they felt that they were unfairly treated. Students may share these anecdotes with peers or with the whole class. Acknowledge their experiences. Explain that not every experience of being treated differently is unfair. Demonstrate this by showing pictures of different people (for example, a toddler, a person in a wheelchair, a physically fit adult) and a mountain. If we wanted to treat everyone equally, we would provide each individual with the same hiking gear and ask them to climb the mountain. Ask students to predict what would happen.

Explain that to reach the same outcome, we must adjust the support we provide.

Next, invite students to imagine that they have accidentally cut themselves and need a Band-Aid. Ask one student where they cut themselves. Place a band-aid where they indicate this imaginary cut to be. Move to the next student, and ask them the same question. But place the Band-Aid over the same place as the first student, regardless of what the second student says. Continue this for some time. Bring students back together and ask them to consider how or whether their Band-Aid helped with the cut they imagined. Just as a band-aid on the arm when the cut was on the knee will not help, explain that teachers sometimes treat students differently because their needs are different.

Connecting With Peers

Friendships play an important function in school belonging and help young people feel satisfied with life in general.

Activity 2: Changing Perspectives

Begin by telling the parable of the blind men and an elephant. Encourage a discussion based on the moral of the story before highlighting that our perspectives are informed by past experiences and other individual and social factors. Emphasise that there is value in discovering other people’s perspectives rather than assuming they are wrong.

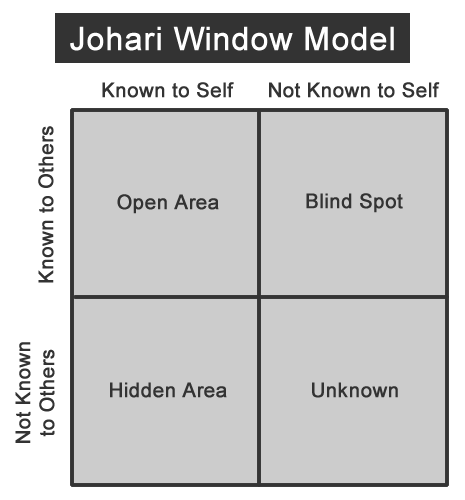

Introduce the Johari window and explain the four quadrants (Public, Blind, Hidden, and Unknown). You may wish to create worksheets with a simple Johari window, or ask students to do this on a sheet of paper.

Ask students to work in twos or fours. Students will first complete Quadrant 1 (Open Area, or public) individually, writing down traits, values, or behaviours about themselves that they believe are known to themselves and to others. Allow about 5 minutes for this. Next, ask students to pass the worksheet clockwise. Allow 3-5 minutes for the students to now write in the Blind quadrant, listing one to two traits, values, or behaviours the owner of the original worksheet may be unaware of.* Rotate the worksheet again and allow everyone in the group to write one trait, value, or behaviour in the Blind quadrant for all group members. When the owner receives their worksheet with others’ comments, allow 5 minutes for students to read and reflect on the comments from their peers. They should then complete Quadrant 3 (Hidden), listing

traits, values, and behaviours only known to themselves. Encourage students to leave the last quadrant blank, but to reflect on what that might look like in the future.

End with a class discussion on what they learned from the activity.

*NOTE: You may want to preface this part of the activity with a discussion on the kinds of traits, values, and behaviours that should be listed: Everything should have a foundation of kindness, respect, and goodwill.

In my conversation with Fiafia, I found that once she felt a better sense of connection with her teachers and peers, she felt happier and more valued, and she enjoyed learning more. It took time, but by the end of her final year at school, Fiafia felt that she was a valued part of her school community.

Finding ways to help young people is an ongoing journey. Share in the comments below what activities and/or strategies you have found to be helpful in this journey.